Jenkins is one of the most common CI tools out there. Almost every developer will have some experience of using Jenkins, but few will say they like it. Why is that?

Some of the criticism of Jenkins is fair, but some are probably not. Jenkins is an open-source tool so it relies on people giving up their time to help move it forward. I don’t want to criticise their work but given how common it is we should ask why some people dislike it and if is that fair?

There are 5 key areas:

- User Interface

- Architecture

- Plugins

- Jenkinsfiles

- Management

User Interface

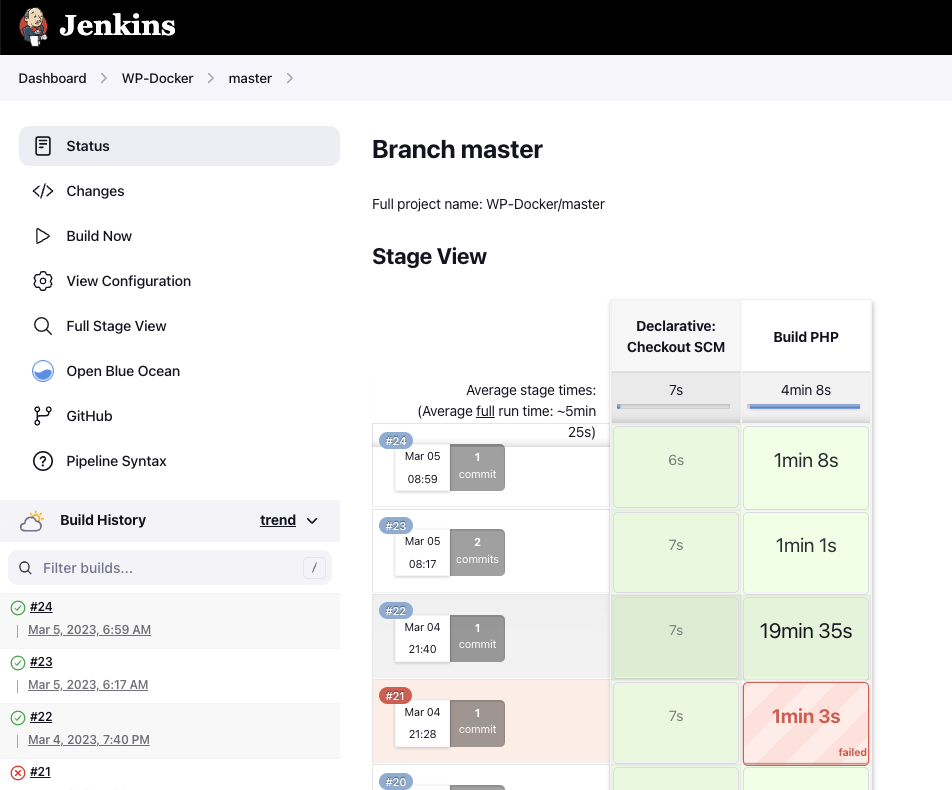

There are no ways about it, the Jenkins UI is not great. It’s dated but functional, mostly.

The biggest problem is that you cannot visualise builds easily with different branch complex flows. If you have too many steps, you need to scroll to the right to see them. If there are parallel branches, it will look like later steps are running out of order.

They have tried to modernise it with Blue Ocean, but that’s a plugin, and you have to shift back to old screens regularly. A modern default UI would be a big help for developers who have worked with other tools.

Architecture

When looking at the Jenkins architecture today, it feels a bit dated. There is a master node and a number of build agents. That’s great since it can scale and you can have different agents for different jobs. You might have a Windows agent, a Linux agent, maybe some for Java and some with JavaScript.

The problem is that these are all virtual machines (or maybe even physical machines). This model is a throwback to data centres and static servers that someone would need to set up. It’s not a bad model, but if we want a new build agent because now we’re going to do some work in Go, we have a lot to set up.

There are ways around this problem; you can use Docker build agents or Kubernetes if you like. There are also ways to spin up EC2 instances or other temporary servers that become build agents for a while and then are torn down. The problem is that these are all plugins. They require extra configuration, and some of it can be not very pleasant to use.

This is how to configure containers with the Jenkins Kubernetes plugin:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

pipeline {

agent {

kubernetes {

yaml '''

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

spec:

volumes:

- name: homelab-java

configMap:

name: homelab-java

- name: build-cache

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: build-cache

serviceAccountName: jenkins-agents

containers:

- name: maven

image: maven:3-openjdk-18

volumeMounts:

- name: homelab-java

mountPath: /homelab

- name: build-cache

mountPath: /root/.m2

subPath: maven

env:

- name: MAVEN_OPTS

value: -Djavax.net.ssl.trustStore=/homelab/homelab.jks -Djavax.net.ssl.trustStorePassword=homelab -Djavax.net.ssl.trustStoreType=jks

command:

- cat

tty: true

- cat

'''

}

}

stages {

stage('Build') {

steps {

container('maven') {

dir('workflow') {

sh "mvn clean package"

}

}

}

}

}

}

That’s YAML inside a Groovy file! The chances of a mistake are high and it’s just not easy to work with. To make it worse, there are multiple ways to do this, depending on the plugin you use and the syntax you choose so good luck finding documentation on the errors.

Plugins

There are Jenkins plugins for everything. If you want to manage an Azure environment or link to Jira, or use an obscure built tool, there’s a plugin for that. The problem is that they are inconsistent. Some are extremely useful and powerful, while others are a bit limited.

There are also some that are just basic functionality. Jenkins’s own pipeline functionality is just a plugin, as is Git and integration with any third-party services. This model allows you to customise your Jenkins however you like, but it also means Jenkins is not very useful when you first start it. You will spend a while installing plugins before doing it anything. There are ways to automate that process, but, of course, you need a plugin for that.

The other problem is that the plugins are often not well documented. You can use Groovy pipelines in multiple formats, Jenkins build steps or scripts to run a build in Jenkins so obviously the plugin developers cannot document it for every scenario. That means you either need to know how to translate the documentation or keep searching until you get the answer.

I don’t want to be hard on Jenkins plugins. They are built by people who were kind enough to open-source their code, and we all benefit. The problem is that they are vital to using Jenkins, and all the different options mean that you can’t always find simple answers.

Jenkinsfiles

In the old days you had to set up a Jenkins build set by step in the UI. It was a pain and no-one liked it. Yes, you could create a build script in your project and just run that but then how would you know where it failed?

Jenkinsfiles are a massive step forward. They allow us to write the build steps in a file in the code repo and Jenkins will just run it. The problem is that this file uses a Groovy Domain Specific Language (DSL). I know there are some people that like Groovy but I am not one of them and Groovy is not a common language that people use nowadays.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

pipeline {

tools {

maven 'maven'

}

stages {

stage('Test') {

steps {

sh 'mvn test'

}

}

}

}

It is even more complex when you add in that there are two subtly different styles of pipelines. You can have a scripted or declarative pipeline, both are called a Jenksinfile and both are written in Groovy, but the scructure is different. This presents a challenge when reading documentation and teaching people how to use a Jenkinsfile.

Look at this example of a scripted pipeline, and can you see the difference with the declarative pipeline above?

1

2

3

4

5

node {

stage('Test') {

sh 'mvn test'

}

}

Simple differences like needing a steps block for a declarative pipeline are important. If you are a developer who normally does other things and you look up some documentation, these differences are not obvious, and they will cause the pipeline to fail.

These issues make it harder for developers to approach a Jenkinsfile. Remember that most developers are not just working on Jenkins. They have an application to build and need to run a pipeline, the complexities of Jenkins make it harder to work with.

Management

One of the biggest complaints I hear is from developers saying, ‘we need this plugin’ or ‘that Jenkins node is down again’ or ‘Jenkins cannot connect to x’. The issue is that Jenkins is down, or something needs to be installed.

These issues are always in organisations where Jenkins is a ‘service’ and managed centrally. This is almost always a management problem. One team ‘owns’ Jenkins and changes require approvals from many teams. This can cause much frustration for developers because the tool they have been given is not working for them.

The thing is, it’s not usually the fault of Jenkins. Centrally managed IT services are always slow-moving and cause much frustration. Jenkins is a free piece of software and giving each team their own costs nothing.

The alternatives

So what about the alternatives. The answer is that there are a lot of CI tools out there but not quite the same as Jenkins.

Tools like Github Actions, Cricle CI, AWS Code Build and others are all easier to use but come with their own considerations. They all offer configuration as yaml files and use Docker as their primary means of execution. They are all SaaS solutions so there is no need to worry about servers but you will be paying for the computing time. In addition, if you are working in a closed network with your own Git or servers, you will struggle to connect them, it can be done but you will need to do work, so the no servers advantage quickly disappears.

There are other free tools like Concourse or Drone but they are still not as well used as Jenkins. That means the plugins are not as extensive, the stackoverflow answers are fewer. They are good tools, but you still need to manage them. While they look nicer and are a bit more modern than Jenkins, you will also find it harder to get the staff that know them well.

Is Jenkins actually bad?

Well, no.

Jenkins is showing it’s age, but the core is still good. It would be nice to have a new UI and a replacement for the Jenkinsfile, but the system’s core works well. As well as refreshed package of standard plugins and new documentation would all help.

Badly managed tools will be problems regardless of the tool so it’s hard to blame Jenkins for internal problems.

Overall, Jenkins is a free software that does its job well. It’s not perfect, but I’m glad it’s here.